The pace of life in Bhutan is slow and it’s an ideal place to reinvigorate your body, mind, and soul. The environment is such that you feel one with nature and relearn to enjoy the small things in life.

I spent ten days relearning life’s pace and the importance of stillness. Buddhism, which is the prominent religion of the land, permeates every aspect of life here and inconspicuously influences habits and culture.

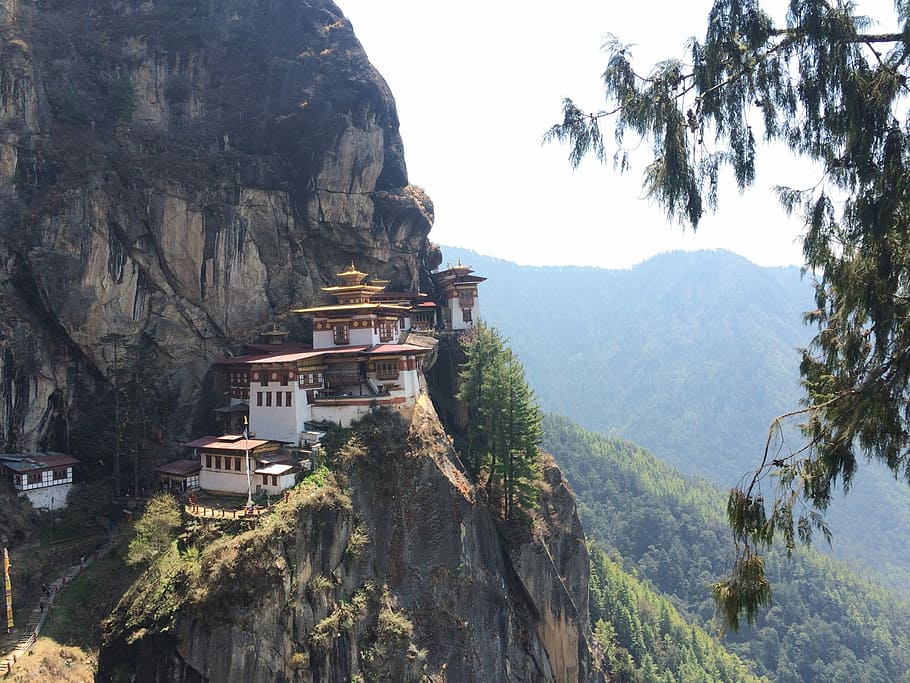

I went to monasteries, met monks and nuns, ate local organic food, breathed in the fresh air and savoured the small pleasures of life.

My favourite was an unplanned stop, en route to a rafting trip near Punakha. When I saw farmers sowing paddy on the roadside, I could not help the urge to get dirty and work! The locals were hesitant at first, wondering if I would indeed be helpful, or a nuisance. The guide helped me persuade them, and to both our delight we proved him right by sowing an entire field. There was laughter, fun and cheerful banter; smiles, hand-shakes and a roll in the mud! The language of smiles is universal and we all communicated without knowing each other’s language. A connection was made.

Art fascinates me and looking at all those beautiful monasteries with ancient artwork, I was tempted to try out a workshop to create a Mandala.

A mandala is a geometric configuration of symbols, that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically; a time-microcosm of the universe. Though it was originally meant to represent wholeness and a model for the organizational structure of life itself—a cosmic diagram that shows us our relation to the infinite, the world that extends beyond and within our minds and bodies.

In the Buddhist spiritual tradition, mandalas are not just an offering of the universe to the Guru; it is also employed for focusing the attention of practitioners as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation.

With the help of a local monk, I learnt the significance of the process of creating a Mandala. We used coloured sand and coloured rice grains on a large canvas, kept on the floor. Didn’t realise I spent three hours creating! In the end, we were allowed to take photos and very significantly, were told to dismantle what we had just made. A very important life lesson was learnt of the “impermanence of things” in life; also, a conviction that you can recreate what you created earlier.

According to art therapist and mental health counsellor Susanne F. Fincher, we owe the reintroduction of Mandalas into modern Western thought to Carl Gustav Jung, the Swiss analytical psychologist. In his autobiography, Jung wrote: “I sketched every morning in a notebook a small circular drawing, … which seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time. … Only gradually did I discover what the mandala really is: … the Self, the wholeness of the personality, which if all goes well is harmonious.”

— Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, pp. 195–196.

Jung recognized that the urge to make Mandalas emerges during moments of intense personal growth. Their appearance indicates a profound rebalancing process is underway in the psyche. The result of the process is a more complex and better-integrated personality.

The Mandala serves a conservative purpose – namely, to restore a previously existing order. But it also serves the creative purpose of giving expression and form to something that does not yet exist, something new and unique. … The process is that of the ascending spiral, which grows upward while simultaneously returning again and again to the same point.

Bhutan is beckoning, come explore!